A research team from the Royal Holloway University of London is testing a new tool that aims to determine positions more accurately than GPS systems.

During a trip on the London Underground, Dr. Joseph Cotter from the Cold Matter Centre at the Royal Holloway University brought along special equipment, including a vacuum chamber made of stainless steel, several billion rubidium atoms, and a laser. These tools are being used to develop a quantum compass—an instrument that harnesses the behavior of subatomic particles to help pinpoint locations accurately, as reported by the Guardian on June 16.

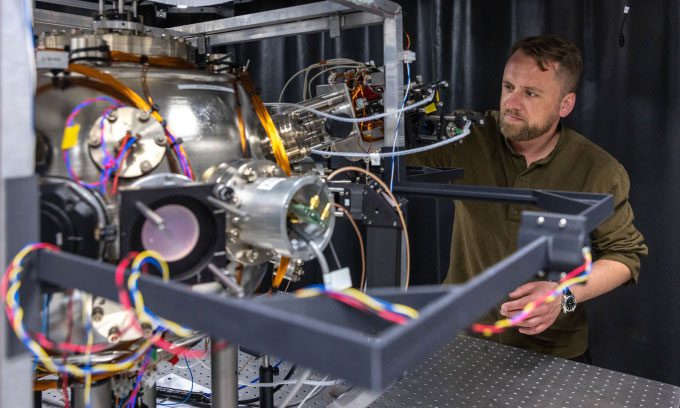

Dr. Joseph Cotter with his underground equipment, the quantum accelerometer used for navigation. (Photo: Thomas Angus).

The goal of the quantum compass is to surpass or enhance current methods for locating airplanes, cars, and other objects. These methods often rely on Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), such as GPS.

However, GNSS devices are vulnerable to adverse weather conditions and noise sources, and they do not function underwater or underground. Their signals are often obstructed by tall buildings or other obstacles. The objective of the project team at the Royal Holloway University is to create a device that can accurately determine its own position without relying on external signals.

“You won’t have to worry about losing signals or being blocked by skyscrapers. You’ll have more confidence in knowing exactly where you or your vehicle is at any given moment,” said Dr. Aisha Kaushik from the Cold Matter Centre.

The focus of the quantum compass is an accelerometer capable of measuring an object’s change in velocity over time. This information, combined with the object’s starting point, helps calculate its future position. While mobile phones and laptops also have accelerometers, those versions cannot maintain accuracy over long periods.

Quantum mechanics offers a highly accurate method: Measuring ultracold atoms. At extremely low temperatures, atoms behave in a quantum manner, acting both like particles and waves. “When atoms are in a supercooled state, we can use quantum mechanics to describe how they move. This allows us to make precise measurements to determine how our device’s position is changing,” Cotter explained.

Quantum positioning system on the London Underground. (Photo: Royal Holloway University of London).

The equipment that Cotter took on the London Underground (during track testing, not during service) involved rubidium atoms placed in the vacuum chamber at the center. The research team then used a powerful laser to cool these atoms down to near absolute zero (-273.15 degrees Celsius). Under such conditions, the wave properties of the rubidium atoms are affected by the acceleration of the vehicle carrying the device. These small changes can be measured accurately.

Cotter noted that while the new system works well in the laboratory, it needs to be tested in more challenging conditions to become an independent, portable device usable in remote or complex locations. Underground tunnels are ideal for this mission. In fact, the London Underground system could benefit from the new quantum sensors, as they would eliminate the need for the hundreds of kilometers of cables currently used to track the positions of 540 trains operating during peak hours under the city.