Scientists have spent nearly three decades cleaning up 177 massive tanks of radioactive waste at the Hanford Site in Washington State, USA. And they have only just begun. This process could take another 60 years and cost $550 billion…

Hanford holds some of the most alarming records. It has become one of the most dangerous places on the planet! Reporters have dubbed it the most polluted site in the Western Hemisphere. It is also home to one of the largest construction projects in the world.

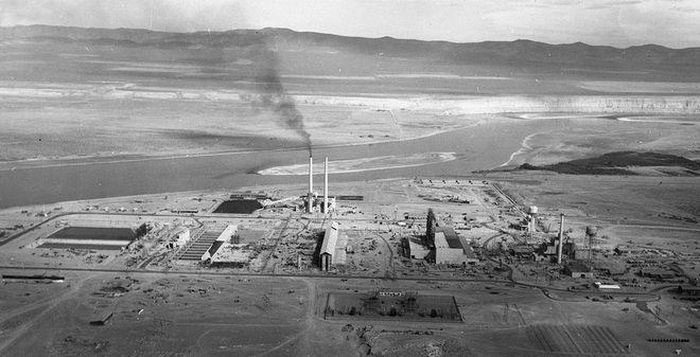

The Hanford Site, located in the central southern part of Washington State, produced plutonium for nuclear weapons during World War II and the Cold War. The Hanford Vit plant was designed to clean up the waste from that nuclear legacy. (PHOTO: U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY)

At the Hanford Site in the central southern part of Washington State (Northwest USA), 177 gigantic tanks lie beneath a sandy soil, filled with radioactive remnants from 44 years of nuclear material production.

From World War II (1939-1945) to the Cold War (1946-1991), the Hanford nuclear production complex generated radioactive plutonium for over 60,000 nuclear weapons, including the atomic bomb that devastated Nagasaki, Japan, in August 1945.

This vast site ultimately contaminated the land and groundwater and left behind 212 million liters of toxic radioactive waste—enough to fill 85 standard Olympic-sized swimming pools. Decades after this site ceased plutonium production, the U.S. government is still struggling with how to clean it all up—’erasing’ a dangerous legacy of radioactive pollution from the war era.

Today, the 1,518 square kilometer site, nearly half the area of the state of Rhode Island, is a quiet expanse of sagebrush and soft grass outside Richland, Washington. However, beneath it lies a troubling issue for the United States.

Cleaning up these enormous tanks of radioactive waste is expected to take another 60 years and cost approximately $550 billion.

The underground steel and reinforced concrete tanks are grouped into “farms” beneath the plateau, while the nuclear reactors are shut down. Scientists have identified about 1,800 contaminants inside the tanks, including plutonium, uranium, cesium, aluminum, iodine, and mercury.

The waste is what remains from a brutal era during World War II and the Cold War. Established in 1943 as part of the Manhattan Project [a U.S. government initiative to create the most destructive weapon in history] at Hanford, this site housed Reactor B, the world’s first full-scale plutonium production reactor.

Beginning in 1943, experts at Hanford pioneered industrial-scale methods to chemically separate plutonium from irradiated uranium, and they did so safely.

Their initial bismuth-phosphate process produced plutonium “buttons” the size of hockey pucks, which were used in the first atomic bomb test in history—called Trinity on July 16, 1945, in New Mexico; and later in the bomb dropped on Nagasaki (Japan) in 1945. Over the years, they discovered five more processes, culminating in plutonium uranium extraction (PUREX), which has become the global standard for nuclear fuel processing.

For over 40 years, radioactive waste from plutonium processing has been pumped into 177 underground storage tanks at the Hanford Site. (PHOTO: U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY)

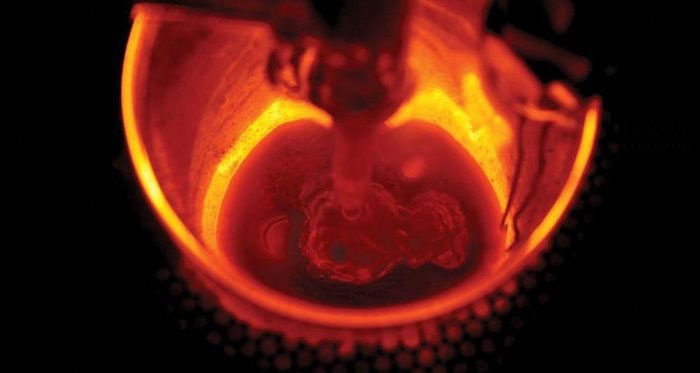

Each tank contains a mixture of toxic liquids, solids, and sludge. No tank among the total of 177 has the same waste composition (after it has become a mixture). (PHOTO: U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY)

Each of these methods generated distinct waste streams, which were stored on-site and then pumped into underground storage tanks. When some of the older single-shell tanks began to leak years later, workers pumped the liquid into newer, more secure double-shell tanks. Chemical reactions occurred when various waste products mixed together, resulting in each tank being filled with a unique mix of liquid, solid, and sandy sludge.

As a result, by 1987, when Hanford ceased plutonium production, the ‘tank farms’ contained a lethal amount of long-lived radioactive chemicals, metals, and isotopes.

No two of the 177 tanks are exactly alike (as each tank has its own waste mix), but all of them pose significant public risk. The site borders the Columbia River, which nourishes the region’s potato fields and vineyards, is a spawning ground for salmon, and provides drinking water for millions. So far, many corroding tank cracks have leaked about 4 million liters of toxic waste. Some experts say it is only a matter of time before more waste seeps through the cracks.

60 Years and $550 Billion to Clean Up the “Painful Legacy”

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), the agency overseeing the Hanford area, has aimed for decades to treat and “vitrify” or glassify the waste in the tanks for safer handling.

Vitrification is a rapid cooling process of a liquid environment to prevent ice crystal formation. In simple terms, vitrification is the solidification of a liquid. In the case at Hanford, it is the solidification of radioactive waste into glass blocks.

With the waste solidified in this manner, harmful radioactive particles cannot flow into the river or seep into groundwater. To enhance containment, the most hazardous radioactive blocks are placed in steel drums, which can then be deposited in a dry, geologically stable underground vault. Vitrification plants have been successfully built and operated in Belgium, France, Germany, Japan, Russia, the UK, and the USA.

The challenge is that Hanford’s waste is the most distinctive among nuclear waste types globally, both in composition and volume. Before they can turn it into glass, workers must accurately determine what is inside each tank and then develop a glass production formula for each tank. It is worth noting that each of the 177 tanks has its own unique waste contaminants.

This is a monumental task and one of the largest engineering projects in the world. At the center of the work is a vast series of facilities known as The Waste Treatment and Immobilization Plant, also referred to as The Hanford Vit Plant, spanning about 25 acres.

The $16.8 billion Hanford Vit Plant is designed to separate and process 212 million liters of radioactive storage tank waste from the Hanford Site. (PHOTO: WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF ECOLOGY)

The U.S. Department of Energy now estimates that it will cost $16.8 billion to complete the Hanford Vit Plant, built by Bechtel National and a series of subcontractors.

According to scientists, the Hanford Site, born and constructed frantically in the heat of World War II, is now slowly grappling with the task of handling its ‘war legacy’ with a murky destination.

Will Eaton, who leads the vitrification mission at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) of the U.S. Department of Energy in Richland, stated: “Hanford is a one-of-a-kind site in the world. While processing radioactive waste is a long and costly process, a clear roadmap is necessary.”

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, even after the completion of the Vit Plant, the actual cleanup will take many more decades. In the 2019 report on “Life Cycle Scope, Schedule, and Costs of Hanford”, the Department estimated that the purification and processing of Hanford’s waste could cost up to $550 billion and extend over an additional 60 years.

The vitrification process of radioactive waste at Hanford must be handled according to its “own formula.” (Photo: PACIFIC NORTHWEST NATIONAL LABORATORY)

Regarding the vitrification process for radioactive waste at Hanford, U.S. experts stated: Processing Hanford’s radioactive waste involves vitrifying it into solid glass blocks for safer handling. Other sites worldwide have successfully used vitrification to stabilize their nuclear waste.

However, the waste from Hanford is complex and diverse, so scientists need to devise a unique vitrification “formula” for each batch of waste. Ultimately, the stainless steel vitrified blocks of low-activity waste will be buried at the Hanford site. High-level vitrified waste will be transported to an undisclosed location.

During the peak plutonium production period at Hanford, workers discharged approximately 1.7 trillion liters of liquid waste into land treatment sites, which evolved into heaps of toxic chemicals underground, including carcinogens such as hexavalent chromium (Cr (VI)) and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4).

No one can predict when Hanford will begin the vitrification of its most toxic waste. The U.S. Department of Energy has stated that most of the technical issues that previously stalled construction have been resolved, but it “cannot predict with certainty” when the facilities for pre-treatment and vitrification of hazardous waste will be completed and operational. The timeline depends on various factors, including federal funding, contractor efficiency, and technological progress.

In September 2019, the U.S. Department of Energy issued a “serious” warning for the entire state of Washington if Hanford does not process high-level hazardous waste by 2033; and if the Waste Treatment Plant is not completed by 2036.

Although the U.S. Department of Energy has implemented some temporary measures, such as pouring concrete into waste storage tanks to stabilize them and prevent leaks, they still assert that vitrification is the safest and most reliable method for managing radioactive waste at Hanford.

There is a grim reality that most of the workers involved in the Hanford cleanup today will not live to see the final results. A person in their 40s (in 2018) would be 100 years old by 2078—the year the U.S. Department of Energy plans to complete its Hanford cleanup efforts.

Leckband, the Chair of the Hanford Advisory Council, emphasized the importance of having a long-term vision. “The most important mantra we must keep repeating is that we have to clean up Hanford thoroughly to ensure the safety of the public, for those who will drink water, breathe air, and eat vegetables across the entire Pacific Northwest. We do this not just for ourselves but for future generations.”