187 years ago, Robert Cocking made a parachute jump from a balloon at Vauxhall Gardens from a height of 1,500 meters and died shortly thereafter.

On October 22, 1797, a crowd gathered at Parc Monceau in Paris to witness a daring display. André-Jacques Garnerin, a Frenchman, was preparing to make a parachute jump from a balloon using a new parachute design he had created.

Unlike previous designs that used fixed wooden frames, Garnerin’s parachute was made of silk and folded like an umbrella. The parachute was closed before Garnerin ascended with the basket attached below. Upon reaching an altitude of about 900 meters, he opened the parachute and cut the tether to the balloon.

Immediately, Garnerin and his basket began to fall. The basket swayed violently during the descent, crashing to the ground and bouncing back into the air. Despite the abrupt landing, Garnerin was not injured, only feeling nauseous. He landed about a kilometer north of the park and was quickly brought back to the starting point, where he was welcomed by a cheering crowd celebrating his first success.

Among the crowd was Robert Cocking, an English watercolor artist with a passion for balloons. Cocking was interested in the improved conical parachute design by Sir George Cayley, a pioneering aviator honored as the “father of aviation in the period 1809-1810.” Cocking believed that with this improved design, he could replicate Garnerin’s success but with a gentler landing.

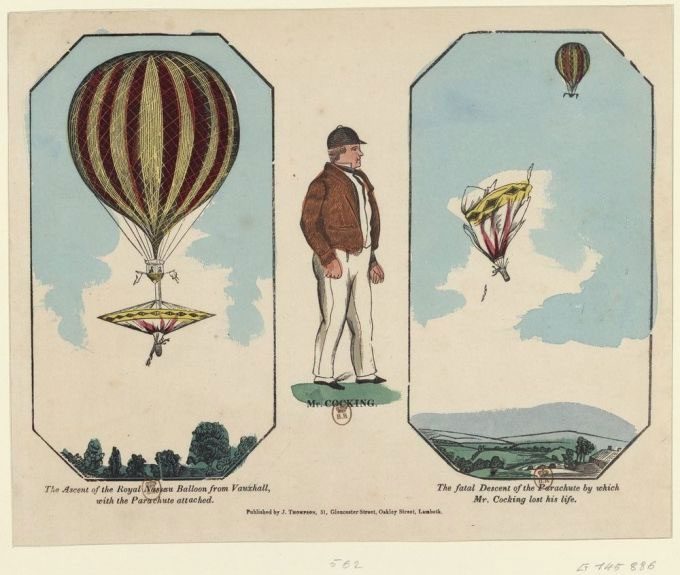

Cocking spent several years developing his improved parachute based on Cayley’s design. It was an inverted conical parachute with a circumference of 32.6 meters. Attached below the parachute was a wicker basket that would carry Cocking. This basket was to be tethered to the balloon by a cord that could be cut at the appropriate moment to free the parachute from the balloon.

Cocking sought permission from Charles Green and Edward Spencer, the owners of the Royal Nassau balloon, to test his invention. Although Cocking was 61 years old, not a professional scientist, and had no parachuting experience, the balloon owners agreed. They advertised the event as the main highlight of the Grand Day Fête at Vauxhall Gardens.

On the afternoon of July 24, 1837, at Vauxhall Gardens, Robert Cocking took flight. Cocking was in a basket hanging beneath the parachute, attached below the basket of the balloon operated by Green and Spencer. Cocking hoped to reach an altitude of 2,400 meters, but the weight of the balloon along with the parachute and three people made ascent difficult. At an altitude of 1,500 meters, Green informed Cocking that he could not ascend any higher due to safety concerns.

“Very well,” Cocking replied, “if you really won’t take me higher, I’ll say goodbye.” Shortly afterward, he pulled the release pin to detach the parachute from the balloon. Freed from the weight, the balloon soared upward.

For a few seconds, Cocking’s parachute descended quickly but steadily and without swaying, just as he had anticipated. Then, suddenly, the entire apparatus flipped upside down, like an umbrella caught in a strong wind. It fell straight to the ground. When people found him in the shattered basket, he was still alive, mumbling incoherently. Ten minutes later, he passed away.

A drawing depicting the Royal Nassau balloon ascending with Cocking’s parachute, and falling to cause fatality. (Image: Amusing Planet).

According to one account, following the tragedy, some unscrupulous individuals stole pieces of Cocking’s parachute, as well as his wallet, watch, medicine box, glasses, shoes, hat, and coat buttons. A local pub owner charged six pence to view Cocking’s mangled body.

Despite the unfortunate ending and being recognized as the first fatality from parachuting, many regarded Cocking as a man of science who contributed to the field of aviation. Subsequent analysis revealed that the design of the parachute was reasonable, but its structure was weak.

Cocking’s death was a setback for parachute development. This tragic incident highlighted the importance of thorough testing and the need for professional expertise in the field. After Cocking’s death, parachuting became unpopular. The activity was only performed in shows at fairs and circuses until the late 19th century when harnesses and emergency parachutes were developed, providing better safety.