According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States, the Omicron variant is currently the dominant strain of Covid-19 in the country. Nearly three-quarters of new infections are attributed to this variant—a sixfold increase compared to Omicron infections from the previous week, just a month after the first Omicron case was reported in the U.S.

Scientists have made significant strides in understanding the origins and spread of Covid-19, but this is partly why the Omicron variant is so surprising: its origins are difficult to comprehend, as it does not stem from other prominent strains like the Delta variant. The confusion surrounding the origins of this new variant creates additional barriers to treating it.

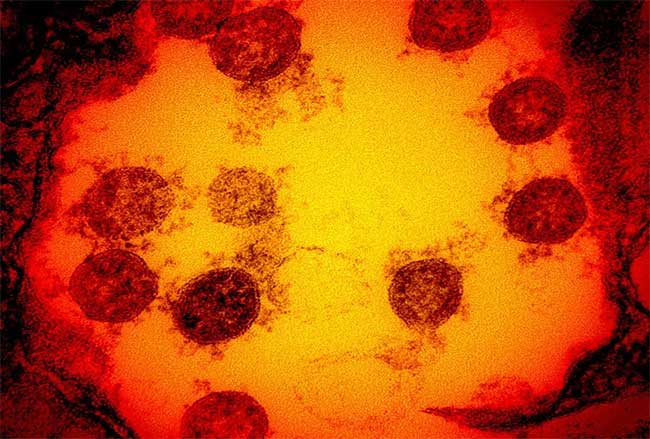

In addition to its extremely rapid transmissibility, the Omicron variant is alarming because it has 30 mutations located near the spike protein, which are the protruding parts resembling spikes on the spherical core of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Since existing mRNA vaccines are designed to train the immune system to recognize these spikes as intruders, mutations on the spike proteins may help the Omicron variant evade the body’s defense efforts and partially escape the immunity conferred by current vaccines.

So how did Omicron develop so many mutations on its spike proteins without any intermediate evolutionary steps through other variants? Scientists have hypothesized about how this might have occurred, although no hypothesis has been reassuring.

First, it is important to note that we are all aware that mutations will occur with a virus, to some extent. As SARS-CoV-2 is defeated by the human immune system and the vaccine shield we create, surviving viruses tend to become mutated to evade human immune efforts. These survivors then pass on those traits to their offspring viruses through replication. Thanks to genetic technology, researchers have been able to study these mutated strains and learn about the “family tree” of SARS-CoV-2, or the relationships between all related variants.

Healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients in the U.S. (Photo: AP)

And here is where the strange story unfolds. There is a significant gap in the evolutionary timeline of the Omicron variant.

Typically, the sequence characteristics in the genome of any virus can be matched in databases with other strains so that experts can infer their origins. Scientists trace these “family trees” to learn more about a virus’s origins, hoping that this information will help them defeat it. However, the most recent identifiable sequences in the genome of the Omicron variant date back over a year, to mid-2020. This means that scientists cannot link it to currently circulating strains. Yet, they are certain that the Omicron strain is very different from the original SARS-CoV-2 strain that swept the globe in early 2020.

So what explains this gap? Where did the Omicron variant come from?

One hypothesis suggests that Omicron developed in a Covid-19 patient with a compromised immune system. Although there is no direct evidence to support this, scientists know that viruses can become stronger in the body of a person with a weakened immune system because they circulate longer—continuing to mutate as they evade the patient’s compromised immune defenses. A virus that circulates for months in the body of an immunocompromised patient could develop superior survival skills by building defenses against human antibodies.

Of course, these are just theories—there is no proof that Omicron originated from an immunocompromised patient. These studies and theories merely indicate that such a development could have occurred.

Dr. William Haseltine—a renowned biologist in the fight against the HIV/AIDS pandemic and currently the Chairman of the global health organization Access Health International—mentioned another widely discussed possibility. That is, the Omicron variant emerged from a process known as reverse zoonosis, which is a situation where a virus originating from another animal jumps to humans, then returns to animals, and subsequently jumps back to humans again. The Covid-19 pandemic originated from the first step of that process (jumping from animals, possibly bats or pangolins, to humans), and the hypothesis suggests that this virus somehow jumped from humans to animals and then back to humans.

Image of the SARS-CoV-2 virus under a microscope.

However, Trevor Bedford, a virologist and professor at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, expressed skepticism about the Omicron variant originating in animals because he does not see residual genetic material from those animals in its genome, but rather human RNA insertion. This “suggests that it evolved in humans.”

In response, Dr. Haseltine wrote to Forbes that this hypothesis “makes complete sense and could very well be the case.” Pointing out the diverse range of animal species that have been infected with Covid-19, he noted that such dual transmission between species has been observed before, leading to a new mutation in the spike protein.

Professor Bedford speculated that the mysterious origins of the Omicron variant could be simply explained by its unclear origins. Many places on the planet where Covid-19 is inadequately monitored, especially in South Africa (where Omicron was first identified), may have allowed a strain to proliferate multiple times in one of those regions without detection—at least until it spread beyond that area.

Although the Omicron variant is more transmissible than other SARS-CoV-2 strains, it does not appear to be more deadly. However, experts believe it will overwhelm the U.S. healthcare system due to the sheer number of infections, with some individuals certainly becoming severely ill.