At this time, scientists, who are theoretical experts in various fields, are trying to hypothesize how the ring around the dwarf planet Quaoar exists.

Data collected from recent telescopic observations reveal that a small planet in the distant region of our solar system has a dense ring surrounding it. Scientists are struggling to explain why this is the case.

Simulation of a wandering dwarf planet in the Solar System.

The celestial body Quaoar, sometimes regarded as a dwarf planet, is one of approximately 3,000 celestial objects orbiting the Sun beyond the orbit of Neptune, with a diameter of 1,110 km (the seventh largest among dwarf planets, with Pluto and Eris being the largest).

Observations of Quaoar conducted from 2018 to 2021 show that this dwarf planet has a ring located farther away than previously imagined by scientists. This was confirmed in a press release from the European Space Agency (ESA) after they utilized ground-based telescopes and a new space instrument, the Cheops telescope, to gather data.

Based on conventional reasoning, all material that makes up Quaoar’s dense ring should have condensed to form a small moon. But that is not the case.

The European Space Agency stated: “Initial results suggest that the frigid temperatures at Quaoar may play a role in preventing icy particles from sticking together, but further investigation is needed.”

Beyond the Roche Limit

Before these new observations of Quaoar, most scientists believed that planets could not form rings beyond a certain distance. This is a mechanical rule applied to celestial bodies, widely accepted that material in orbit around a planet will form a spherical object (commonly referred to as a moon) if it orbits far enough from the planet. However, that moon would be torn apart if it moved closer to what is known as the “Roche Limit,” a point at which the tidal forces of the planet exceed the gravitational force holding the moon together.

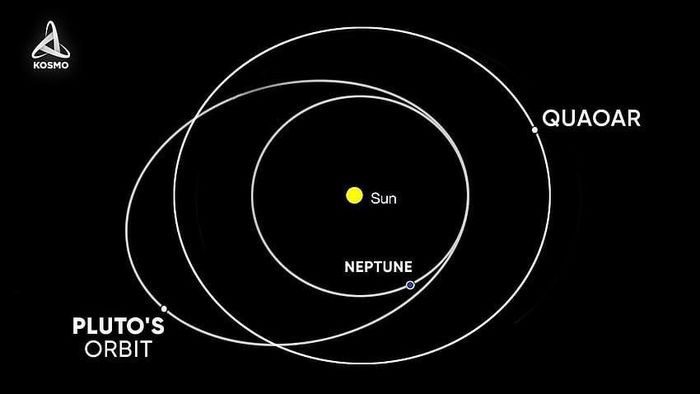

Orbit of Quaoar between Neptune and Pluto.

For example, all of Saturn’s rings are located within the Roche limit of that planet. However, the puzzling aspect of Quaoar is that its ring lies beyond the Roche limit, in a region where material should typically form a moon.

Giovanni Bruno from the Astrophysical Observatory of INAF in Catania, Italy asserted: “According to our observational results, the classical notion that dense rings only exist within the Roche limit of a celestial body must be radically revised.”

How to Study a Dwarf Planet at a Great Distance?

According to ESA, the data collection revealing the enigmatic ring of Quaoar has been a reason for celebration. Due to the small size of the planet and its distance from Earth, researchers aimed to observe it using the occultation method. In this method, a planet is observed by waiting for it to be backlit by a sufficiently bright star.

According to ESA, this can be an extremely challenging process because the telescope, planet, and star must be perfectly aligned. This observation was made possible thanks to recent efforts by the space agency to provide an unprecedented detailed map of the stars.

ESA also utilized the Cheops telescope, launched in 2019. Cheops typically studies exoplanets or celestial bodies outside our solar system. However, in this case, it focused its observations on the closer target, Quaoar. Although it is in the Solar System, its orbit around the Sun is even farther than Neptune, which has an orbit of about 44 AU (1 AU is the average distance from the Earth to the Sun).

Isabella Pagano, director of the Astrophysical Observatory of Catania at INAF, stated: “Initially, I was somewhat skeptical about the feasibility of doing this with the Cheops telescope. But it worked.” According to ESA, observations from Cheops marked the first time that one of the farthest planets in our solar system was observed using a space telescope.

Subsequently, researchers compared the data collected by Cheops with observations from telescopes on Earth, leading to their surprising discovery.

Bruno Morgado, a professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil and the head of the analysis, stated: “When we put everything together, we saw that the brightness decreased not due to Quaoar itself, but indicating the presence of material in a circular orbit around it. We realized we were observing a ring around Quaoar.”

|

Quaoar was discovered by astronomer Chad Trujillo on June 5, 2002, when he identified it in images obtained from the Samuel Oschin Telescope at Palomar Observatory the night before. This discovery was reported to the Minor Planet Center on June 6, with Trujillo and colleague Michael Brown credited for this finding. At the time of its discovery, Quaoar was located in the constellation Ophiuchus, with an apparent magnitude of 18.5. Its discovery was officially announced at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society on October 7, 2002. Quaoar orbits at a distance of about 43.7 astronomical units (6.54 × 109 km; 4.06 × 109 mi) from the Sun, with an orbital period of 288.8 years. Quaoar has a low orbital eccentricity of 0.0394, meaning its orbit is nearly circular. Its orbit is tilted moderately with respect to the ecliptic at about 8 degrees, typical of the population of small classical Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs), but particularly among the larger KBOs. Quaoar is not significantly perturbed by Neptune, unlike Pluto, which is in a 2:3 orbital resonance with Neptune (Pluto orbits the Sun 2 times for every 3 orbits completed by Neptune). Quaoar is the largest object classified as a cubewano or classical Kuiper Belt Object by both the Minor Planet Center and the Deep Ecliptic Survey (although the larger dwarf planet Makemake is also classified as a cubewano). Quaoar occasionally moves closer to the Sun than Pluto, as Pluto’s aphelion (the farthest distance from the Sun) is outside and below Quaoar’s orbit. In 2008, Quaoar was only 14 AU away from Pluto, making it the largest known object closest to Pluto in 2019. The rotation period of Quaoar is uncertain, and two possible rotational periods of Quaoar have been suggested (8.64 hours or 17.68 hours). Based on light curve observations of Quaoar made from March to June 2003, its rotation period was measured to be 17.6788 hours. The albedo or reflectivity of Quaoar can be as low as 0.1, still much higher than the lower estimate of 0.04 for 20000 Varuna. This may indicate that fresh ice has vanished from Quaoar’s surface. The surface has a moderate red color, indicating that Quaoar reflects relatively more in the red and near-infrared spectrum compared to blue. Other Kuiper Belt objects like Varuna and Ixion also exhibit moderate red colors in their spectral profiles. Larger Kuiper Belt objects are often much brighter because they are covered in fresher ice and have higher albedos, resulting in a more neutral color. An internal heating model through radioactive decay in 2006 suggested that, unlike 90482 Orcus, Quaoar may not be capable of sustaining a subsurface ocean at the core-mantle boundary. |