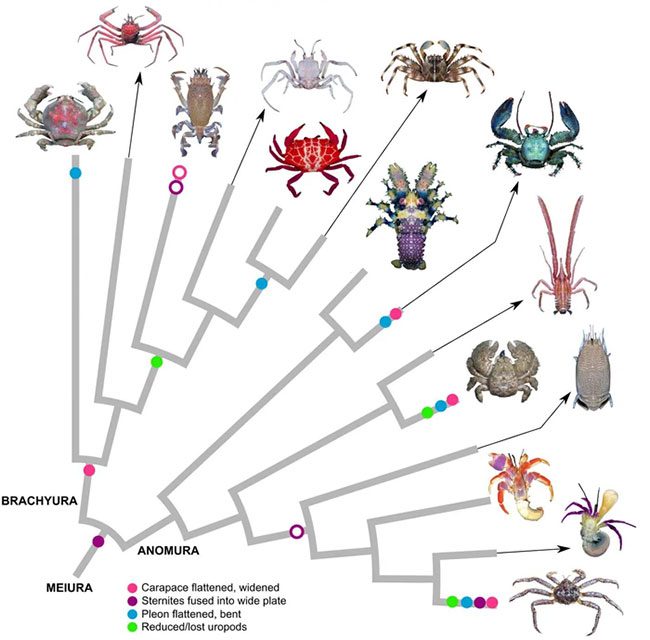

The crab-like body plan has evolved so successfully that it has occurred at least five times independently.

The complex evolutionary history of our planet has produced countless strange and wonderful creatures, but none has intrigued evolutionary biologists—or divided taxonomists—quite like the crab.

In a study published in 2021, researchers sought to analyze the evolutionary history of crabs and concluded that the defining characteristics of crab-like body structure have evolved at least five separate times among decapod crustaceans over the past 250 million years.

This repeated evolutionary process resulting in a crab-like body plan happens so frequently that it has a name: carcinization.

The defining characteristics of crab-like body structure have evolved at least 5 times.

Carcinization is an example of a phenomenon known as convergent evolution, where different groups of organisms independently evolve similar traits. This is why both bats and birds have wings. Interestingly, the evolution of crab-like bodies has occurred multiple times among species that are very closely related.

Why evolution continues to shape and adapt the bodies of many organisms to resemble crabs remains a mystery, but we know that there are thousands of crab species thriving in nearly every habitat on Earth, from coral reefs and abyssal plains to estuaries, caves, and forests.

Crabs also exhibit a remarkable diversity in body size, with the smallest being the pea crab (Pinnothera faba), measuring just a few millimeters, while the largest, the Japanese spider crab (Macrocheira kaempferi), can reach nearly 4 meters across its claws.

With their rich species diversity, varied body shapes, and abundant fossil record, crabs are an ideal group of organisms for studying trends in biodiversity over time.

Crabs also exhibit a remarkable diversity in body size.

Crustaceans have repeatedly shifted from a cylindrical body shape with a large tail—characteristic of shrimp or lobsters—to a flatter, rounder shape more akin to crabs, with a tucked tail beneath their abdomen.

As a result, many crustaceans have evolved to look very crab-like, such as the king crab, which has a crab-like body structure but actually belongs to a closely related group of crustaceans known as “false crabs.”

The most obvious difference between “true crabs” and “false crabs” is the number of walking legs: true crabs have four pairs of legs, while false crabs have only three pairs.

Both true and false crabs have independently evolved broad, flat, hard shells and tucked tails from a common ancestor that lacked these features, according to an analysis published in March 2021, led by evolutionary biologist Joanna Wolfe from Harvard University.

Many crustaceans have evolved to look very crab-like.

Like many other subjects, evolutionary biologists have numerous ideas to explain this, but there is currently no definitive answer regarding the phenomenon of carcinization.

When a trait appears in an animal and persists over many generations, it is a sign that the trait is advantageous for the species. This is the basic principle of natural selection. Crab-like animals come in various sizes and thrive in many habitats, from mountains to deep seas. Joanna Wolfe states that their diversity makes it difficult to identify a single common benefit for their body structure.

Wolfe and her colleagues proposed several possibilities in a 2021 paper in the journal BioEssays. For instance, the tucked tail of crabs, compared to the tail of lobsters, may reduce the amount of vulnerable meat accessible to predators. Additionally, the round, flat shell may help crabs roll onto their sides more efficiently than the cylindrical body of lobsters.

However, more research is needed to test these hypotheses, Wolfe said. She is also attempting to use genetic data to better understand the relationships among different decapod crustacean species, to more accurately pinpoint when various “crab” lineages evolved and to distinguish the factors driving the process of carcinization.

The crab body shape may help animals be more agile in developing specialized roles for their legs beyond walking, allowing crabs to easily adapt to new environments. Some crab species have adapted their legs for digging through sediment or swimming in water.

Most species that have undergone the carcinization process have developed hard, calcified shells to protect them from predators—a clear advantage—but there are also some crab species that have abandoned this protective shell for unclear reasons.

Moving sideways may seem silly, yet it allows crabs to be extremely agile, enabling them to escape quickly in either direction without losing sight of a predator, should one appear. However, side-stepping is not observed in all crab lineages that have undergone carcinization (some spider crabs move forward), and some hermit crabs that have not undergone carcinization can also move sideways.