In 1923, in an essay titled “Daedalus or Science and the Future“, John Burdon Sanderson Haldane – a British-Indian physiologist and geneticist, made a prediction about a concept he called Ectogenesis.

Ectogenesis means “extracorporeal pregnancy“. Haldane predicted that organisms, including humans, in a future world would no longer need to carry pregnancies. Instead, they would create systems, machines, and artificial wombs that would allow for the fertilization of eggs and nurture embryos until birth.

Humans in a future world will no longer need to carry pregnancies.

Haldane’s idea later became one of the inspirations for Aldous Huxley to write Brave New World in 1932, which depicts a dystopian future where identical children are born from a massive incubator in the heart of London.

A closer example is the 1999 film The Matrix by the Wachowski siblings, which tells the story of a world controlled by artificial intelligence. In that world, there are fields with millions of womb-like pods. Inside them are humans trapped from birth, living in a virtual reality and never truly born.

In his vision, Haldane believed that by 2051, humans would master Ectogenesis technology. By 2070, up to 70% of children would be born from artificial wombs or pods.

Artificial Wombs for Animals

Can humans achieve the timeline set by Haldane? That remains a question that scientists are still uncertain about.

However, for animals, we have made certain advancements. In 2017, two groups of scientists in the USA, Australia, and Japan successfully developed artificial wombs capable of nurturing sheep embryos.

These biological bags, called EVE, contain a sterile liquid similar to amniotic fluid. EVE allows the fetus, in this case, sheep, to breathe through the umbilical cord and absorb nutrients naturally.

Five years later, a group of Japanese scientists announced that they had also successfully developed an artificial womb, this time for sharks.

Researchers at the Churashima Research Center and Churaumi Aquarium in Okinawa successfully nurtured two lantern shark embryos, developing them to the fifth month and giving birth from these artificial wombs.

The slender-tail lantern shark (Etmopterus molleri) is a small shark species belonging to the subclass Elasmobranchii. More than 80% of these species are listed as threatened in the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List.

The lantern shark itself is a species for which there is no statistical data on its population. However, successfully nurturing this species in an artificial womb also means that scientists can nurture other elasmobranch species.

Thus, this is undoubtedly a significant breakthrough, primarily for the conservation of wild marine life, and secondly for the development of artificial womb technology and Ectogenesis.

A Mother Shark Dies, Leaving 6 Living Embryos

The story began when a group of local fishermen on Okinawa Island, Japan, caught a lantern shark. When they brought the fish aboard, they kept it in a cooler filled with seawater. Unfortunately, the fish died after six hours of traveling back to shore.

The fishermen knew this was a rare specimen, so they donated the deceased lantern shark to the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. Scientists there subsequently performed an ultrasound on the shark’s body.

They were surprised to find that it was a female shark and that she was pregnant. Inside her womb, the lantern shark had six embryos that survived after her death.

This is a female shark and she is pregnant.

Like many other shark species, the lantern shark has a unique form of reproduction called ovoviviparity. In this process, the shark does not actually carry the embryos but retains her own eggs. It is still considered an egg-laying fish, but the eggs are kept inside the mother’s body until they are ready to hatch.

This reproductive method differs from live birth in that the shark embryos have no connection to the mother’s body. They do not receive nutrients or gas exchange from the mother shark, and there is no placenta connecting them.

The shark embryos develop thanks to the nutrients stored in the yolk sac. In fact, the shark embryos even cannibalize each other in the mother’s womb to obtain nutrients for their development.

This explains why even after the mother lantern shark died, the six embryos in her belly still survived. Japanese scientists were therefore determined to nurture these embryos using an artificial womb technology they were developing.

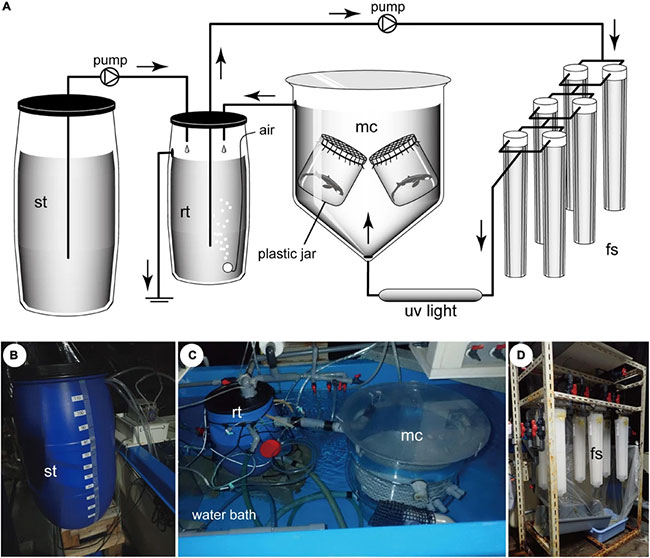

They selected the two most intact embryos, which had eaten the other embryos in the mother shark’s belly, and placed them into the artificial womb system. Each system consists of three chambers, each about 60 cm deep. One chamber serves as a reservoir, another is a filtration system, and the main chamber is where the shark embryos will be nurtured.

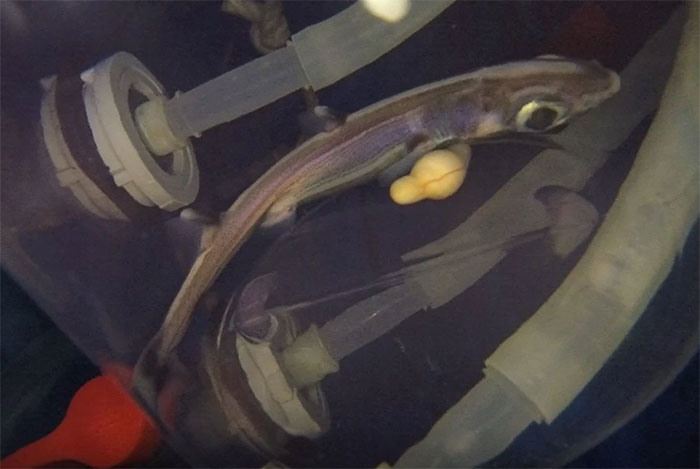

Each chamber is irrigated with a type of “broth-like liquid” similar to amniotic fluid at a steady rate of 10 liters per minute from below. The shark embryos are placed in two separate 500 ml plastic containers within the main chamber, covered with a plastic mesh to allow free exchange of the liquid.

The entire system is maintained at a temperature of 12 degrees Celsius and has an external system providing fresh broth-like liquid continuously.

Regarding the broth-like liquid, or artificial womb fluid, Japanese scientists composed it using shark blood plasma, along with 100 liters of filtered seawater, 46 liters of tap water, and 3.5 kg of urea to achieve salinity and osmolality similar to that of the shark’s womb environment.

A Setback but Still a Breakthrough

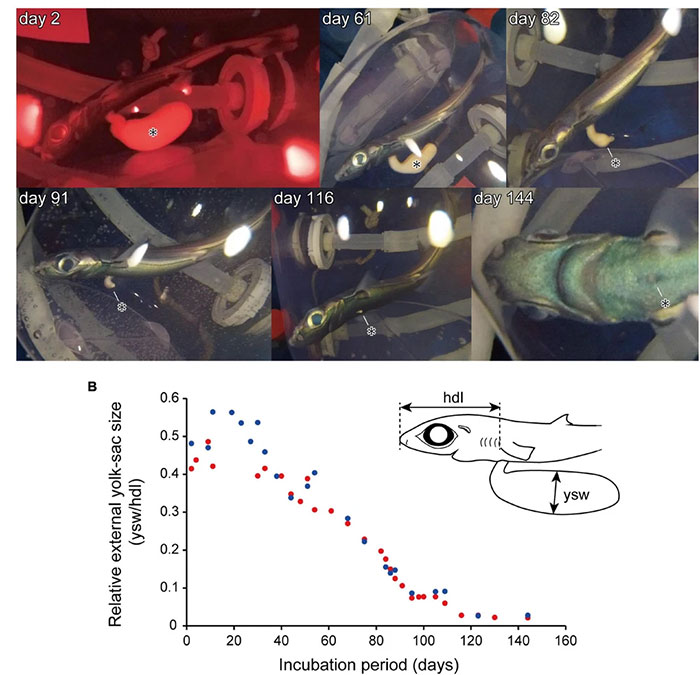

Monitoring results showed that throughout the first month, the embryos of these two shark pups remained completely motionless. This led scientists to initially suspect that they had died.

However, by the second month, the shark embryos began to move within the artificial womb environment. They grew larger, reaching a length of 15 cm. By day 146, the Japanese scientists decided that their first embryo should be “born”.

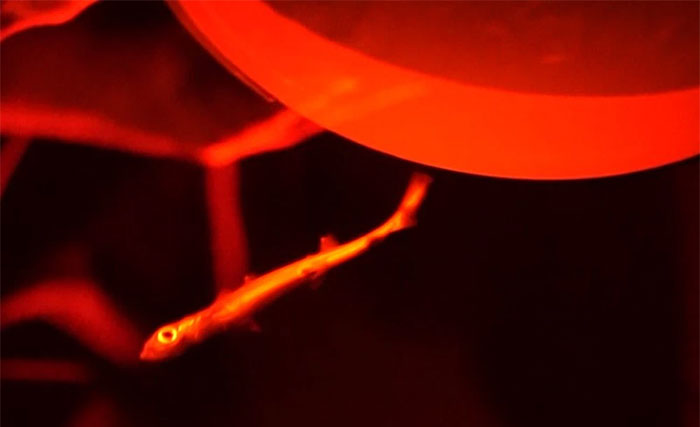

That was when the yolk sac of the embryo had completely withdrawn, and they would transfer this shark pup from the artificial womb to an external seawater tank. The scientists defined this as the activity of “artificial birth“. Unfortunately, the first shark pup could not adapt to the seawater environment and died four days later.

The shark pup while still in the artificial womb.

The moment of artificial birth of the lantern shark.

The second shark pup continued to be nurtured in the artificial womb until day 160. It was born in a similar manner but ultimately also died on day 25.

Despite this, there was progress with this second shark pup as it managed to eat two meals during its short life: one meal of 0.1 grams of shrimp meat on day 2 and another meal of 0.15 grams of mackerel meat on day 9.

Scientists stated that their project was not truly successful, but they achieved a record for nurturing shark embryos in an artificial womb. The total lifespan of these two embryos was 150 and 184 days. In comparison, shark embryos typically only survive 5-7 days in regular seawater.

This also marks the record for the survival of embryos among species in the subclass Elasmobranchii. Therefore, this technology could be applied in conservation units when they want to nurture embryos in breeding programs with a higher success rate.

The total lifespan of these two embryos was 150 and 184 days.

In the future, scientists still need to refine this technology and understand why the sharks born from their artificial womb environment could not survive. Their initial assessment may be that the post-birth seawater environment was unsuitable.

“The remaining technical challenge is how to safely adapt the incubated specimens to the seawater environment after ‘artificial birth.’ We attempted to carry out this process by periodically exposing the specimens to seawater before ‘artificial birth,’ although this method ultimately did not succeed“, the research team wrote.

Nevertheless, we will continue to wait and see when Japanese scientists will refine this artificial womb technology to perfection.

And we also wait to see if Haldane’s predictions will come true by 2051. By then, will we not only have artificial wombs for sharks but also for humans?